My father’s heart fell victim to heredity four years ago.

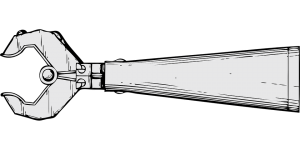

The surgeon placed a stent in his aortic valve to brace

the walls and keep the blood flowing.

I imagine the stent shaped like a bridge to strings,

like the one that bolsters the cello

in the corner of my room collecting dust.

But even before that, he couldn’t pass the physical

to join the Korean War–his heart murmured

something the doctors did not like.

My father’s father died of a heart attack, or

maybe complications of diabetes that betrayed his heart.

He was a musician and a piano tuner,

who sometimes imposed a cello lesson on me,

firmly pressing my fingers to the finger board

nearly 45 years ago on that corner resting cello.

All of his 8 sons played musical instruments.

The 21 year old I work with at the sweet shop,

whose name may be Rob or Mike or John,

is someone I would say has a heart of gold,

but for his laziness, though still an amiable sort.

He has a pair of friends, twin brothers, who

come to pick him up from work and take him home.

One told me that Rob-Mike-John had five heart attacks

when he was only a sophomore in high school.

His doctor said he was lucky to be alive.

My mother’s heart is strong, always has been.

Her mind and body are ravaged by demented

disease, forgetting to allow her to live, but her

heart beats resoundingly under her ribs, her doctor says.

And though the cuffs don’t hurt her any more,

too little flesh on her arms, her blood pressure rocks.

Sans word, thought or flesh, she is pure pulsing heart now.